Softly, Softly, Catch-ee Thunk-y

tl;dr

Don’t catch at the end of a thunk.

I’ve got an app using Redux Thunk, making network requests with the following pattern.

function getFunky = () =>

dispatch => {

// tell app we're getting funky

dispatch(actions.getFunky())

// make the network request

service.getFunky()

// tell app we got funky

.then(funky => dispatch(actions.getFunkySuccess(funky)))

// oh, no! handle lack of funkiness

.catch(error => dispatch(actions.getFunkyError(error)))

}

This seems to make sense as it goes through the several states when making a request.

- the request was made, reponse pending

- the request is done, here’s the result

- the request failed, here’s an error

There’s a problem here, though. What if I successfully getFunky, which then

triggers the getFunkySuccess action, which in turn alters the app’s state in a

reducer, which causes a connected component to rerender, which has a runtime

error?

The catch block catches it, assuming we’re not using error boundaries or any

other error handling. Since we’ve made the assumption that the catch block

was going to handle service layer failures, that means our hypothetical runtime

exception thrown from our component is now being dispatched in getFunkyError

and then probably stored in the app state.

This is weird.

“But Jeremy,” you say, “I’m a reasonable dev. I’ve got a linter paired with PropTypes checks that should be catching basically all of these types of errors.”

OK, good. But…

“Also,” you interrupt, quite rudely, “I’m a strict TDD adherent and I have great unit test coverage. If I’m getting a silly runtime error like this, it’s going to come up in my unit tests way before getting into Redux!”

That’s awesome. I think you’re right and you’ve made excellent points, but we’ve still made a mistake. We haven’t known each other long, so you don’t have to take my word for it.

Here’s a comment straight from the Redux README referring to aync actions like ours.

Do not use catch, because that will also catch

any errors in the dispatch and resulting render,

causing a loop of 'Unexpected batch number' errors.

“But, Dan,” you object, somehow thinking he can hear you through my blog. “I’ve never seen that error before.”

Even so, some people say that this makes it really tough to troubleshoot errors

because the catch is swallowing everything.

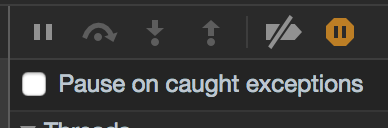

“Yes, that’s what catch is for,” you say, quite sure of yourself. “If I shot

myself in the foot by turning of the linter and skipping unit tests, though, I

could still figure out where it was throwing immediately by just checking this.”

You are a wise and skillful dev. I think we should hang out more often.

Hear me out, though. This is still a little sloppy. The reason for that is, we’re making a dillweed out of you and umption.

function getFunky = () =>

dispatch => {

// tell app we're getting funky

dispatch(actions.getFunky())

// make the network request

service.getFunky()

// tell app we got funky

.then(funky => dispatch(actions.getFunkySuccess(funky)))

// oh, no!

//

// RIGHT HERE is a big fat assumption

//

.catch(error => dispatch(actions.getFunkyError(error)))

}

The assumption we’re making here is that this is catching an error thrown by the

service during getFunky. That’s just not right. We’ve demonstrated that if

we’re sloppy or unlucky, the stack generated by the then block could also

throw and end up in this catch block. Being unlikely or preventable doesn’t

make this good logical flow.

What if we’ve got a bunch of other steps in this promise chain? If they throw,

we end up here again, but it’s not because of the service call failure. Abramov

suggests a fix that subtly shifts things a little closer to what we intended.

Instead of throwing this big catch at the end and assuming it’s catching a

failure of service.getFunky, just use the 2nd arg in the then following it

to more accurately scope the error handling.

function getFunky = () =>

dispatch => {

// tell app we're getting funky

dispatch(actions.getFunky())

// make the network request

service.getFunky()

.then(

// tell app we got funky

funky => dispatch(actions.getFunkySuccess(funky)),

// oh, no!

error => dispatch(actions.getFunkyError(error))

)

}

Now, the branch dispatching getFunkyError is only going to be called when

there was an error getting funky. It’s more predictable and that’s always nice.